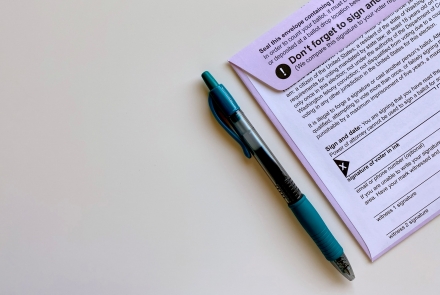

Photo by Tiffany Tertipes on Unsplash

American democracy is under threat

With unusually high levels of mail-in voting and the influence of social media comes a heightened risk of foreign interference in the United States’ 2020 election, Adam Henschke writes.

The 2020 United States presidential election is one of the most unpredictable and closely watched in modern history, with social, legal, and political upheaval happening almost daily. Add to this the loss of trust in polls and predictions following the 2016 shock, shifting voting conditions associated with COVID-19, and a growing recognition that foreign states are engaged in efforts to interfere with American politics, and it is easy to see why it’s attracting such attention.

To say that this election is different from normal is a significant understatement. With these sets of background conditions, this election may well not finish when voting ceases, and special attention must be paid to efforts to interfere with the election even after polling day.

There are several ways that foreign actors may seek to interfere with the presidential election after voting has ceased.

They could use local agents in the United States to print out masses of fake ballots and have them ‘discovered’ a few days after the election in order to sew discord about the outcome. In this case, the idea would not be to create fraudulent votes in order to swing the election toward a particular candidate. Rather, it is to give credence to the idea that particular voting blocs had their mail-in votes actively discarded by opponents.

We have seen President Donald Trump already talking about an apparent bundle of ballots that were found discarded in a river. “Did you see what’s going on?” The President said onstage. “They are being dumped in rivers. This is a horrible thing for our country.”

In particular, he suggested that Trump votes had been targeted. “It was reported in one of the newspapers that they found a lot of ballots in a river. They throw them out if they have the name ‘Trump’ on it, I guess.”

These claims were subsequently rejected by the Wisconsin Elections Commissioner stating that “There was mail found outside of Appleton and that mail did not include any Wisconsin ballots.”

So the United States now faces an election with a population primed to believe that their opposition will do whatever it takes to win, including interfering with the vote count. Mail-in voting is not only happening at the highest level in the country’s history but has been so politicised that it will be assessed through a political lens.

On top of this, the idea has already been seeded in the public mind that votes for a candidate are being found in rivers and ditches. If a foreign actor wanted to undermine the trust in the outcome of the election, this is one obvious way to do it.

A second way that a foreign actor might interfere in the election is to produce and release fake video and audio recordings of the likely next president or their team saying that they committed fraud during the election. An operation like this could utilise ‘deepfake’ technologies.

Deepfake technologies allow for very realistic fake videos and audio to be created, making it appear that a person is saying or doing things that they have not said nor done. They are particularly problematic because they can convince a sector of a population that someone they already mistrust says and does things that confirm biases and further their mistrust.

For instance, with current technology it would be easy for someone with sufficient skill to create a deepfake of President Trump saying ‘of course we threw Biden votes out. How else did we win this election?’, or Democratic candidate Joe Biden saying ‘of course we threw Trump votes out. How else did we win this election?’.

The fear about deepfakes and this election is not novel. Given the background conditions and the ease with which these technologies can be used however, this election seems particularly vulnerable to such attacks.

Finally, in a repeat of the 2016 interference operation conducted by the Russian Internet Research Agency, malicious actors may use social media to amplify and re-enforce the existing beliefs of American citizens. The tactic here is not necessarily to swing votes, but rather to amplify those who already sincerely disbelieve the outcome of the election. These people might be legitimate citizens who honestly believe the outcome is fraudulent.

Foreign actors could then take those beliefs and use social media to make them louder and more prevalent, with the aim of spreading further disharmony and undermining a broad section of the population’s belief in the outcome of the election. All of this would happen after polling day, and so the election is especially vulnerable to attacks after voting ends.

As the election approaches, onlookers should remember the important distinction between voting security and election integrity.

Voting security is concerned with the conditions around voting itself: are votes being recorded accurately, are tallies reliable, essentially are the processes around receiving, recording, and totalling the tallies reliably free from external efforts? In contrast, election integrity is concerned with broader practices and perceptions about the processes and outcomes of elections.

In the United States, given the significant and ongoing public health emergency of COVID-19, voting practices have had to change for many states. Authorities have had to increase mail-in voting, absentee voting, and early voting to allow more people to vote.

Couple these significant changes with a population already facing massive social division and disharmony and you have an election that is extremely vulnerable to foreign interference. A final point to note is that this vulnerability persists regardless of whoever is initially declared winner. No matter who wins in November, foreign interference may well ensure that the 2020 election is a loss for American democracy.

Updated: 14 July 2024/Responsible Officer: Crawford Engagement/Page Contact: CAP Web Team